FSAC Board Director, Jayson Gordon Featured in

Globe & Mail Article

Reposted from The Globe and Mail Robyn Doolittle | April 9, 2020

‘Plan for the worst and hope for the best’: Canada’s funeral industry in upheaval as coronavirus deaths mount

Contingency plans are being made across the country to avoid the fate of places like New York, where mass graves on public land are being considered to accommodate the deceased

In urban centres across the country, crematoriums are preparing to operate 24/7 if needed, cemeteries are taking stock of available land, funeral homes are renting out refrigerated vehicles and officials are drawing up worst-case scenario plans to use arenas as temporary morgues if necessary.

All of this is to avoid the fate of places such as New York, where decision makers are contemplating digging temporary mass graves on public land as city morgues are overwhelmed. So far, more than 4,000 New Yorkers have succumbed to the virus.

In Toronto, contingency plans include looking at existing municipal facilities that could serve as morgues – such as ice rinks, because of their size and ability to maintain cool temperatures – and procuring enough vehicles and drivers to transport bodies.

“These are discussions that none of us like to have … but [we] put the contingency plans in place regardless of how difficult or uncomfortable they are,” said Toronto Fire Chief Matthew Pegg, who heads the city’s Office of Emergency Management.

The federal government has yet to release its projections for how many deaths the country can expect during the outbreak, but last week Ontario Premier Doug Ford said the country’s most populous province is bracing itself for between 3,000 and 15,000 fatalities over the next two years. In Alberta, Premier Jason Kenney said between 400 and 3,100 people could die from the virus. And public health officials in Quebec say that their modelling indicates at least 1,263 people will die from COVID-19 by the end of this month.

These are daunting numbers for Montreal funeral director Bridget Fetterly.

“I hit a low point five minutes ago,” she said Tuesday afternoon – day 27 of the pandemic. “I’ve been working seven days a week more than 12 hours a day for –,” she can’t remember how many days in a row.

Just as the virus has pushed Canada’s health-care system to the brink, the country’s bereavement sector is also feeling the strain. Rules and protocols around transport, funerals and “disposition” of the body – such as burial or cremation, change daily. Ms. Fetterly has had to reorganize her staff into two teams that don’t interact, so that if someone gets sick the whole operation doesn’t need to close.

So far, the Kane Fetterly funeral home has handled three confirmed COVID-19 cases. In these instances, the deceased were cremated immediately and no service was held. But the implications of the virus spread beyond those specific deaths.

Regular funeral services are more complicated now. No more than 10 mourners are allowed to congregate at a time and guests must maintain two metres of distance. These new rules are in place to prevent a situation like what happened in Newfoundland, where at least 167 cases have been linked to a single funeral home in St. John’s.

There are other practical challenges, like the fact that Kane Fetterly’s primary crematorium temporarily shut down this week after staff members tested positive for the coronavirus. Ms. Fetterly was able to make other arrangements, but these types of setbacks are becoming commonplace.

In 2009, the year of the H1N1 outbreak, the federal government prepared a plan to be used in the event of mass fatalities as a result of a pandemic flu. The document includes considerations around cemetery space, additional grave digger staff and recommendations for what happens if the bereavement sector is overwhelmed. “If local funeral directors are unable to handle the increased numbers of deceased and their funerals, it will be the responsibility of municipalities to make appropriate arrangements,” it states.

David Brazeau, the communications manager with the Bereavement Authority of Ontario, said that’s not going to happen in the province, because the industry has been taking steps to avoid this for weeks.

“Arenas being used – that is not at risk of happening in Ontario … as the regulator, we’re instructing our licensees not to – and I’ll put this starkly – stockpile bodies,” Mr. Brazeau said.

Families are being encouraged to proceed with disposition, meaning burials or cremation, as soon as possible, and the regulator is strongly discouraging embalming, which also uses valuable protective gear.

Rick Cowan, the assistant vice president of marketing communications for the Mount Pleasant Group, said the regulator was very clear that it did not want to see a New York City scenario happen in Ontario.

“So, the challenge was put out to the funeral and cemetery industry: What do you have to change in your system, your process, to ensure we don’t have that situation,” Mr. Cowan said.

For his company, which owns and operates 10 cemeteries, nine funeral establishments and four cremation centres in the Greater Toronto Area, that means retooling staff models in the event that they need to operate the crematoriums at all hours of the day. Mr. Cowan added that they aren’t concerned about running out of burial space.

Similar conversations are happening across the country.

Jayson Gordon, the British Columbia representative with Funeral Service Association of Canada, said funeral homes are focused on finding additional capacity, including portable refrigerated storage and utilizing existing space that may have been decommissioned.

In Alberta, equipment is one the sector’s most pressing concerns, said Tyler Weber, the president of the Alberta Funeral Service Association. Already funeral homes are starting to report shortages of N95 respirator masks, hand sanitizer and body bags, he said. And because they are a lower priority than health-care workers, funeral homes don’t have the ability to order new stock. They have been able to access small amounts of protective gear through the province, but this not a long-term solution.

“We are a key stakeholder in this fight against the transmission of COVID-19 that is often overlooked,” Mr. Weber said.

(The Globe reached out to other large Canadian cities – including Vancouver, Winnipeg and Montreal – to discuss pandemic preparedness and in each was told to contact the province.)

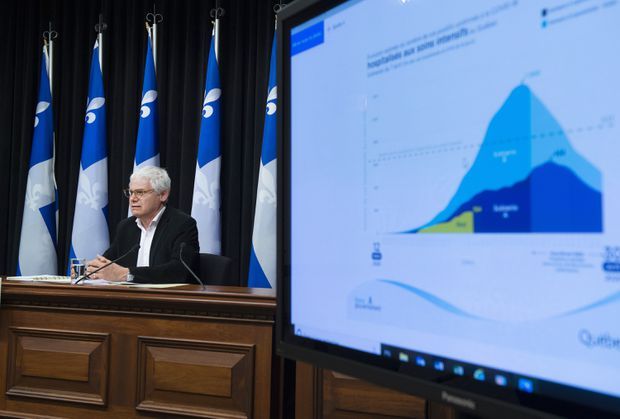

So far, Quebec has been the province hardest hit by COVID-19, with more than 10,000 cases record as of Wednesday. At a news conference on Tuesday, officials announced that under their most pessimistic modelling, the province could expect nearly 9,000 deaths in total.

But David Scott, the executive director of Mount Royal Commemorative Services, which operates three cemeteries and four funeral homes in Montreal, said he thinks the sector will cope.

“My job is to try and anticipate when we will approach an area where our capacity starts to get stretched. We’re not there yet,” Mr. Scott said. “Certainly, in our organization, we have the capacity to deal with a more significant case load if necessary.”

Mount Royal Commemorative Services prepared a pandemic plan back in 2009 during H1N1.

“We hauled it out in early January and have been building off of that for what we’re doing now [with COVID-19],” Mr. Scott said.

Their plan spells out steps for each stage of an outbreak. When COVID-19 was first identified in China, it activated the first phase of their pandemic protocol, which triggered weekly check-ins on the situation among the executive team. After the virus touched Canadian soil, it moved to the next level. Work done at this stage included becoming familiar with the type of contagion they were dealing with, so steps could be taken to protect staff from infection. Next the organization checked in with suppliers and assessed its inventory. Did it have enough protective gear? Cleaning products? Caskets?

So far, things have been running smoothly and the organization has the ability to ramp up cremations and burials if needed.

“Our job is to plan for the worst and hope for the best,” he said.